Picture part of the Forgotten Town Review Article.

Nathanal Updegrapth Walker had been mayor of Wellsville from 1856-1859. History of Columbiana County 1879, - 279.

gen2go/Ohio-River/Section-III

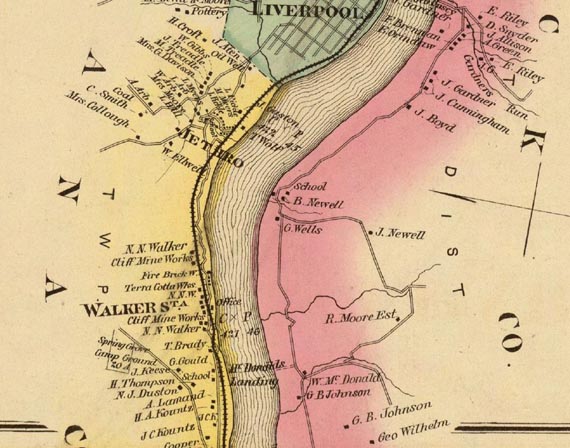

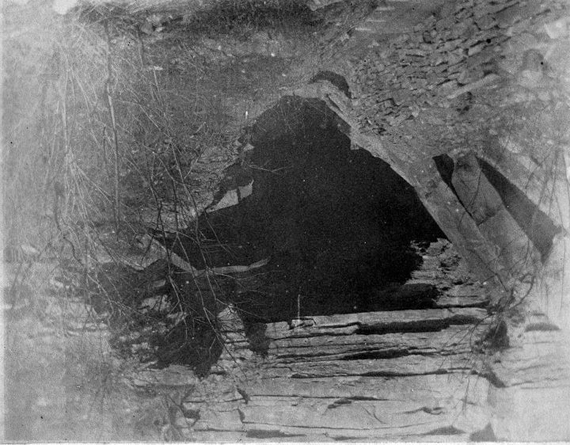

CLIFF MINE TERRA-COTTA WORKS.

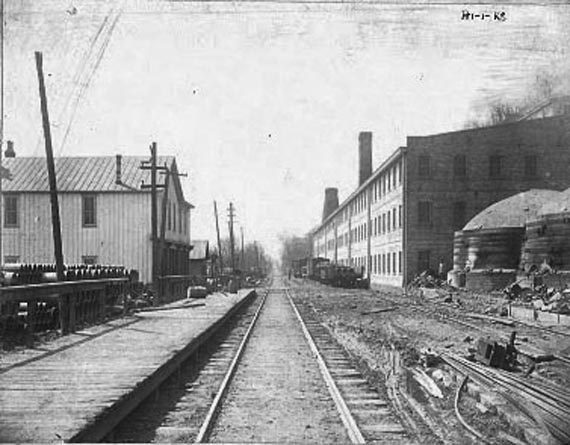

These extensive works, located upon the bank of the Ohio and the line of the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad, midway between Wellsville and East Liverpool, were founded, in 1842, by George McCullough, and are now owned by N. U. Walker.

The works are said to be the most extensive and the oldest of any similar enterprise in America, and manufacture of fire-clay various articles, sash as lire-brick, sewer- pipe, water-pipe, chimney flues, ventilating flue, chimney tops, hot-air flues, cold-air flues, patent chimneys, lawn vases, flower pots, statuary, stove linings, grate, boiler, flue, and flooring, tiles, window-caps, sills, brackets, cornices, etc.

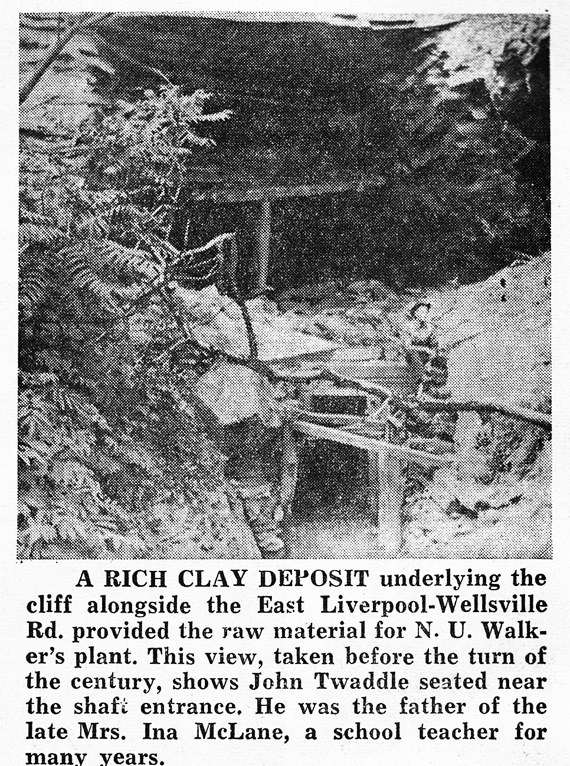

Mr. Walker utilizes the mineral privileges of a 250-acre farm set upon the high slope which overlooks the works, and thence obtains an abundant supply of clay, as well as considerable coal.

Upon his grounds, which have a river front of about half a mile, are, besides the manufactories, tenements for his employees, of whom there are fully one hundred and twenty-five. Upwards of $150,000 are invested in these manufactories, which contribute largely towards the value of productions in Liverpool township, and which have been an important interest in this locality for thirty-seven years. History of Columbiana County 1879, - 184.

HISTORY OF COLUMBIANA COUNTY

(Harold B. Barth Historical Publishing Company 1926)

CHAPTER I

"TOPOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES"

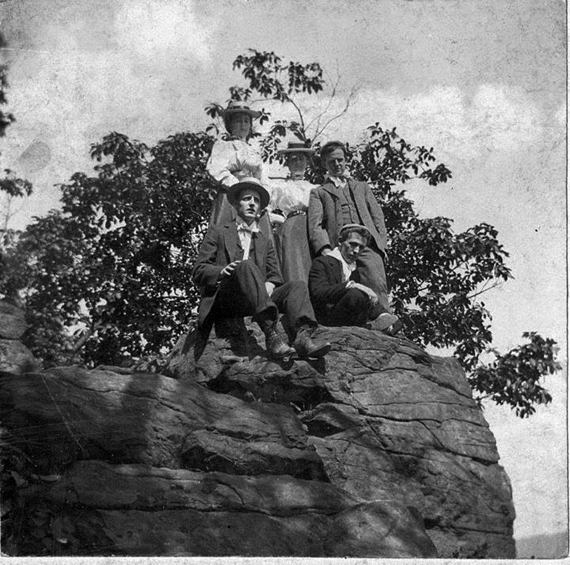

1894, overlooking the Ohio River. Walker's Cliff.[Brady's Bluff] Tim Brookes Collection.

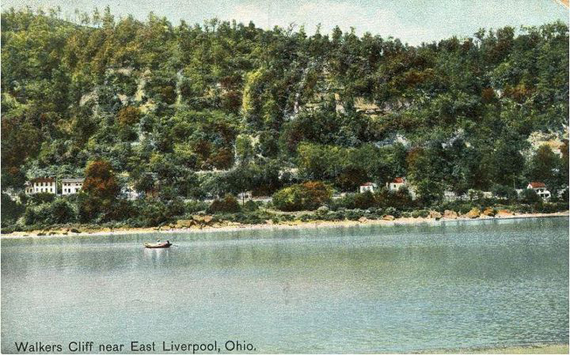

"This is the highest point with the water reaching the greatest depth of any known point on the river. The great Ohio Valley Scenic Electric Line passes along these cliffs which was one of the greatest engineering feats since the construction of the famous Gorge Route at Niagra Falls, N.Y."--card verso. pictures source: East Liverpool Historical Society Published by the Bagley Co., East Liverpool, Ohio circa 1900-1929

Another nearby landmark popped in the news periodically --Brady's Bluff. Although it was cut away considerably when the present East Liverpool – Wellsville Road was built in the early 1950's, the Brady site still holds its reputation as " the highest point along the 980 mile course of the Ohio River from Pittsburgh to Cairo." Capt. Thomas Brady famed pioneer, died in March 1886 at his home near Walker's and was buried in the family cemetery on the bluff.

McCord's History refers to the bluff: "The site of the Walker plant was especially picturesque, at the foot of the highest bluff along the Ohio River between Pittsburgh and Cairo." Excerpt from: The Forgotten Town By Robert Popp. The Eveing Review, Feature Pages East Liverppol, Ohio January 23, 1971.

For anyone interested in Capt. Thomas Brady they can find some information here:

http://www.archive.org/stream/cu31924028846074/cu31924028846074_djvu.txt

http://www.flickr.com/photos/21952092@N02/3109258880/in/set-72157611266424656

The picture the above URL takes you to was originally thought to be the dismantling of a pottery on 2nd Street in East Liverpool, Ohio in 1865. However, that is impossible since gasoline driven trucks hadn't been invented until much later.

A second date is suggested as 1900. Even that date seems unrealistic for the same reasons. The topography doesn't fit anywhere along 2nd St. in Elo.

While we cannot say positively that this is Walker's Works, the topography does fit that location better. If anyone has a positive location for this picture please let us know.

The Forgotten Town

Walkers Was Once A Busy Industrail Plant, Mine

By Robert Popp

THE EVENING REVIEW

FEATURE PAGES

East Liverpool, Ohio Saturday, January 23, 1971

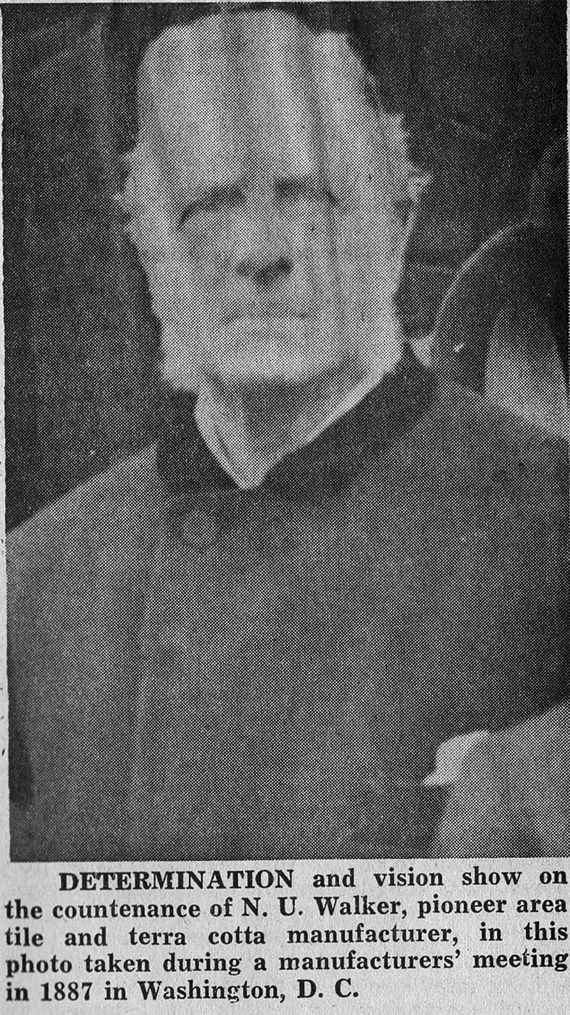

The nearly forgotten community of Walker's, far and away the most famous ghost town in Columbiana County, is a fast fading monument to Nathan Updegraff Walker, one of the self made Giants who strode the earth of Eastern Ohio in the days when laissez faire capitalism which King and the weak and the indecisive fell by the wayside.

N. U. Walker of Wellsville was a man of many parts, but he is remembered best as a shrewd, innovative industrialist who built what was once the nation's largest sewer pipe manufacturing plant on a picturesque bend of the Ohio River midway between Wellsville and East Liverpool.

Several dozen homes clustered around the beehive kilns and clay mine entrance. The community took on the name Walker's, after its major developer, complete with the railway stop, and elementary school, a general store and post office. The plant turned out 24 tons of ware each day, shipping it by rail and river all over the United States - most particularly - to the fast-growing communities of the Midwest.

A historian wrote in 1879 that the plant represented an investment of $150,000 - a major fortune by the standards of that day - and had an average employment of 125.

The concern flourished for 47 years under Walker's ownership and management. Then it was taken over about the turn-of-the-century by a so-called "trust" that gobbled up virtually all the vitrified clay pipe plants in the nation. When N. U. Walker died in 1904 at the age of 81, the plant was in serious decline. It went out of business soon afterward.

There is a story, probably apochryphal, that part of the agreement when Walker sold the plant was that it must continue to operate so long as he lived, providing jobs and income for his faithful employees. The legend says that the plant closed shortly after Walker's death. Close it did, but most likely as a result of serious economic troubles that beset the combine that bought it from Walker.

Many sturdy remnants of the Walker plant still can be found along the Penn. Central tracks below E. Liverpool - Wellsville Rd. and just East of Brady's Bluff. Most are the basis of the beehive kilns in which Walker once produced not only brick and sewer pipe but also ornamental terra cotta, chimney tops, grate tiles, water pipe, chimney flues, ventilating flues, hot and cold air flues, lawn vases, flower pots, statuary, stove linings and window caps, sills, brackets and cornices.

The history of the Walker's tract as an industrial site dates back 129 years. It flourished for 63 years, 47 of them under Walker's operation.

The first development came in 1841, when Andrew Russell build a plant at the site and began producing brick. George McCullough erected another small plant nearby in 1842 for production of tile. Both were attracted by the abundance of clay that could be mined from the steep hillside nearby, a resource that Walker later was to develop to its fullest.

Hill Family Photo Album. From Jack A. Lanam Collection. ELHS.

In 1846, Philip F Geisse of Wellsville, operator of an iron foundry, bought out both Russell and McCullough. He produced bricks in both plants for the next six years.

N. U. Walker, a native of Jefferson County, first appeared on the scene in 1852, when he bought both the Geisse plants. One of Walker's first moves was to enlarge the original plants, a process that was to continue periodically for years.

For the first 18 years, his chief product was brick - fire brick, paving brick and building brick. In 1870, he built another plant in which he turned out sewer pipe, chimney tops and grate tiles. Eight years later, he erected another addition that produced tile, lawn vases, flower pots and statuary.

William B. McCord's authoritative "History of Columbiana County," published in 1905, is the source for the statement that Walker's plant was the largest in the nation. In work published just a year after the founder's death, he said:

"For a number of years, these works were the largest in the nation."

Walker's property covered 300 acres. It had a long frontage on the Ohio River, but authorities differ on the size. Some say the plant stretched for a half-mile along the Ohio. Others say it's frontage was a full mile.

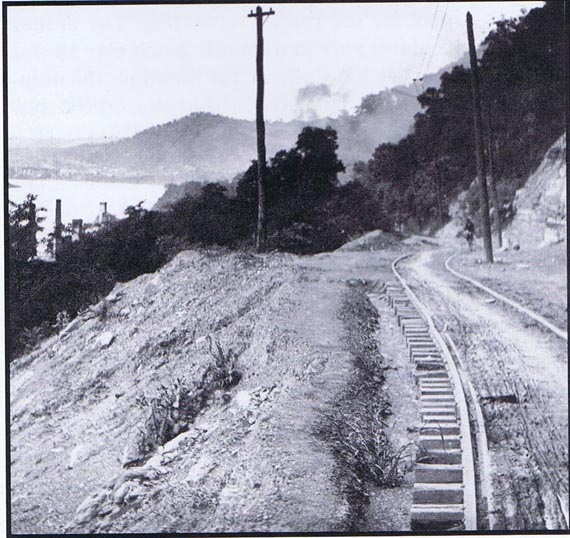

The single track of the Cleveland and Pittsburgh railroad ran hard by the front of the Walker plant. A crude road also bisected the industrial site. Steamboats tied up on the riverfront to take on cargoes of Walker's products. The bustling community turned out 20 tons of sewer pipe and brick each working day, along with another 4 tons of costlier products such as statuary and terra-cotta. The yield from the "captive" clay mines was so large that Walker also shipped summit to other manufacturers.

McCord referred to the plant as the Walker works. In an 1879 "History of Columbiana County" published by D. W. Ensign and company of Philadelphia, the plant was termed "The Cliff mine Terra Cotta Works." In its latter days, the concern had the formal name, N. U. Walker Clay manufacturing company. A few years later it became a part of the American Sewer Pipe Co., which made its headquarters in New Jersey, the so-called "trust" that took over virtually all the nations vitrified clay manufacturing plants.

Despite the scope of his plant, Walker found time for many side interests. He was born in Mt. Pleasant in Jefferson County, son of a pioneer family. For many years his father, Lewis Walker, was cashier of a bank operated in Mount Pleasant by the Society of Friends, popularly known as Quakers. His mother was Anne Updegraff, daughter of Nathan Updegraff, a pioneer miller in southeastern Ohio.

Walker was named for his maternal grandfather, but throughout his adult life he used only his two initials - never the full names. In every newspaper account, court record and history dealing with his life and times, is referred to simply as N. U. Walker. It was in his obituaries that there came the revelation that his full name was Nathan Updegraff Walker.

Walker was educated at a Friends school in Mt. Pleasant. He was married first on June 6, 1848, to Sarah Jane Miller. In 1854, he was married to Evelyn Kimball Brown of Canfield.

Although born a Quaker, he later became a member of the Methodist Episcopal church. He served as an ordained preacher of the denomination for more than 25 years. He served on the building committee for the Methodist Episcopal church at Wellsville. For more than 50 years, he was a master Mason, a member of Riddle Masonic Lodge of East Liverpool.

Walker also was a busy amateur geologist. He help the early development of Taylor University at Upland, Ind., and served for many years on its Board of Trustees. Late in life, he donated his geological collection to Taylor University. The university named the gift the "Walker geological collection" and conferred upon the donor the honorary degree of doctor of divinity.

Walker also was credited with founding the old Spring Grove Camp Meeting Ground on the hilltops between East Liverpool and Wellsville. The Walker family maintained a cottage at the grounds for more than 40 years. Walker spent virtually every summer there except in the year before his death. His 1903 journey to Spring Grove was canceled because his wife was ill.

Walker served for many years as president of the camp meeting Association and usually manage the summer assemblies, in which noted evangelists spoke to throngs of visitors.

Walker died on Monday, June 6, 1904 at the home of his son, Col. Lewis Walker at Meadville, Pennsylvania. He was 81. The Colonel, a son by the second wife, and Mary E. Walker of Wellsville, were his only surviving children. A son, James M. Walker, died in 1902, and another daughter, Alice K. Walker, died in 1872.

The funeral service was held June 8 at the Methodist Episcopal church in Wellsville, with representatives of most of the leading families of the area attending. Burial was in Springhill Cemetery at Wellsville.

Judging from historical references as well as contemporary newspaper accounts, the Walker Works hit its peak in the last quarter century before 1900. Old newspaper files of that era are replete with accounts of the comings and goings of N. U. Walker, along with many references to his plant in the community is surrounded it.

The Evening Review of 1885 carried a "Walker's" column occasionally, listing the visits of the inhabitants of the village, their social doings and illnesses. It also carried a lengthy account of young Walker's resident who was injured mortally in a fall from a retaining wall. Brought to East Liverpool, evidently suffering from severe internal injuries, he died in one of the local hotels a few days later.

N. U. Walker in his plant jumped into the news prominently in February 1886, when the County commissioners named him as defendant in a civil action, alleging his operations were blocking the right-of-way for the Wellsville - E. Liverpool Rd., a rutted track that was muddy and dusty by turns.

[The trolley tracks in the picture were post 1886. Picture courtesy of Wellsville Historical Society.

Charges and counter - charges flew back and forth for weeks. Then the story died away after a report in March that the commissioners and Walker had conferred and apparently had reached an amicable settlement of the court action.

In 1886, Thomas F. Anderson left his post as general manager of the Walker works and joined Isaac W. and Homer S. Knowles and John N. Taylor in forming the Knowles, Taylor and Anderson Co. plant in East End for the production of vitrified products. It was also fated to be taken over by the "sewer pipe combine," although Anderson remained as manager for the concern until 1902.

The so-called combine that came into being in 1899 took over not only the Walker plant and Knowles, Taylor and Anderson concern, but virtually every other vitrified products firm in the East. For instance, it gobbled up plants in Hancock County, as well as the U.S. Fire Clay Co. at Lisbon in the John Lyth Works in the East End of Wellsville. The Lyth concern, organized just 18 years previously, employed 200 in manufacturing of sewer pipe.

But McCord noted; " The new owners promptly furnished the anti-trust agitators of Wellsville with an argument against combines by dismantling the plant and removing the machinery elsewhere. The buildings and kilns as well as the valuable clay deposits in the hills adjoining were allowed to stand idle."

In January 1904, just five months before Walker's death, Ohio Valley newspapers reported that the "trust" - the American Sewer Pipe Co. - was in serious financial difficulty. The concern already had " closed most of its plants in the vicinity of New Cumberland and Toronto" and was preparing to go into the receivership, the newspapers said. They also reported that the firm had " not paid a dividend since it was organized."

But the community of Walkers still was flourishing shortly after the death of its founder. A contemporary newspaper account said Mrs. Mary Magillivary of Wellsville have been named by the Township Board of Education to teach at Walkers School.

The "History of Columbiana County" by H. B. Barth, published in 1925, also terms Walker's plant "the largest of its kind in this country." Barth also credits Walker with manufacturing the first paving brick in the Ohio Valley. His history says it was Walker - made brick that was used about 1877 to pay the west side of Walnut Street, part of one of the first Street - paving projects in East Liverpool.

Barth dates the sale of the Walker Works in 1899, and adds that the concern changed hands " with the stipulation that it would be operated as long as he lived." The plant was abandoned not long after the founder's death.

Barth, now curator of the East Liverpool historical Society Museum and an authority and regional history, wrote about N. U. Walker and the Walker plant with the authority of first - hand knowledge. He remembers seeing Walker at the time the plant was flourishing. He sometimes road to Wellsville in a surrey driven by his maternal grandfather Enoch Bradshaw. The precarious narrow road passed through the center of the Walker Works, and Barth can remember the proprietor striding towards his office, " the tall well-built man with a beard who always wore high hat and a shallow tail coat . . . "

Walker's about 1890. WHS

Additional information on the picture from the Blog "Looking Out My Window," by Old Nib"

http://thevilleview.blogspot.com/2010/01/nu-walker-clay-plant. html

Barth's grandfather did his banking in Wellsville in those days because East Liverpool was without a financial institution. In the days shortly before the turn of the century, Barth was a small, wide-eyed boy as he accompanied his grandfather.

He had vivid memories of the trips to Wellsville and all the landmarks along the way including Walker's. The Wellsville Road of that day had no resemblance to the four-lane concrete ribbon along which cars now speed at 70 miles an hour better. And the path of the highway was much different.

Barth retraced parts of the route a few weeks ago, pointing out the circuitous route the road followed before the turn of the century. At a point on what is now church street in West End, the roadway turned north, then west, descending the steep slope to the bottom of Jethro Hollow. There was no fill across the mouth of the hollow, as there is now, so the roadway followed the natural contour of the land. Deep within the hollow, the roadway cross the stone arch bridge to the West side of the run. Inquiry with some the old time Jethro residents disclosed that the stone arch bridge was covered with new fill when the present Wellsville Road was built in the early 1950's.

Once the West side of the run, the roadway followed the little stream almost to its mouth. Then it turned do West again, near the single-track railroad. There were no houses then in Jethro Hollow area below what is now Shadyside Avenue. Barth remembers only tree covered hillsides on the sheer embankment on either side of the stream.

The Walker plant ruins are centered on a spot almost directly across the River from the Homer Laughlin China Co. Plant. A sign warning "Rock Slides" on the Wellsville Road is a convenient landmark for westbound motorists. If the motorist walked the south berm of the "super road" at that point, he will be able to discern many brick columns, some as high as 4 feet. The ruins are in a grove of trees only 20 to 30 feet from the right -of -way.

Barth said what remains primarily are the foundations and supports for the old beehive kilns. Some of the bricks are conventional size. Others are foot longer, made especially for kiln construction. Most of the brick work still is sturdy. It would require more than a casual shove to break the bricks away from the mortar that holds them.

Barth walked along the railroad tracks to look again at the ruins of the old plant. He had passed the site countless times in the past on walking jaunts with the late Lee C. Cooper, East Liverpool insurance agent. Cooper taught school at Walker's for one term before the turn of the century.

Walkers is one ghost town that not only is dead, but buried. Virtually all of its site was covered by various types of railroad and highway construction. The final encroachment came in the 1950's when a tremendous earth fill was made to carry the new four-lane highway. When the latest highway job was finished, most of Walkers had vanished.

Barth remembers there were 35 to 40 houses in the Walker's community in its heyday. He also remembers being inside the plant, a confusion of workmen and strange sounds.

Barth pointed out that the Walker's site, sheltered by high cliffs and lying in the river's big bend. is unusually warm in winter. Prior to the turn of the century - before construction of the first Ohio River dams - there was a wide sandy beach on the Ohio side of the river at Walkers, a favorite fishing and swimming spot. He does not recall that the plant was subject to frequent flooding, but the river's pool was much lower then the year-round.

Hill Family Photo Album. From Jack A. Lanam Collection. ELHS.

He remembers that when he was a small boy two tremendous rocks "the size of houses" tumbled over the cliff and went into the river close to Walker's. They were removed by a U. S. Government "snag boat," which specialized in taking obstructions out of the river.

Because of the huge volume of products turned out in Walker's heyday, Barth believes some of its ornamental terra cotta went into window caps and cornices of many famous buildings in many parts of the U. S.

N. U. Walker's son, Col. Lewis Walker of Meadville, became rich and famous in his own right, Barth recalls. An attorney, he helped obtain a patent for the inventor of the zipper and in return he obtained a share in the company. Barth recalls visiting the younger Walker in Meadville and exchanging memories of the Col.'s father.

Barth remembers that Col. Walker was passing through East Liverpool one Sunday and decided to attend services at a local church. When the ushers passed the collection plate he dropped in $1000 check. The church officials classified the generous gift as a "joke" or "fake" because they did not recognize the Walker name. But when they took it to the First National Bank, Thomas H. Fisher, the president, told them the story and added: "We'll honor his check even if it is for $10,000.'"

The East Liverpool historical society Museum has one momento of the plant that once flourished on the river bank. It's a piece of sewer pipe found years ago between the river and the railroad tracks stamped "Walkers Ohio."

The site of that once flourishing community and industrial plant lies deserted now, with the remainns of the old kilns covered by vines enshrouded by trees.

It seems like a very good spot for historical marker, one that would help future generations remember, N. U. Walker and his works.

This site is the property of the East Liverpool Historical Society.

Regular linking, i.e. providing the URL of the East Liverpool Historical Society web site for viewers to click on and be taken to the East Liverpool Historical Society entry portal or to any specific article on the website is legally permitted.

Hyperlinking, or as it is also called framing, without permission is not permitted.

Legally speaking framing is still in a murky area of the law

though there have been court cases in which framing has been seen as violation of copyright law. Many cases that were taken to court ended up settling out-of-court with the one doing the framing agreeing to cease framing and to just use a regular link to the other site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society pays fees to keep their site online. A person framing the Society site is effectively presenting the entire East Liverpool Historical Society web site as his own site and doing it at no cost to himself, i.e. stealing the site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society reserves the right to charge such an individual a fee for the use of the Society’s material.